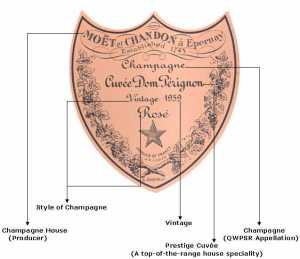

Champagne labeling laws differ from other parts of France because the entire region falls under a single AOP, the protected term ‘Champagne’ and the wines are categorized according to styles rather than designations. Here the status of the producer is more important than the vineyard sites.

To distinguish between the numerous different styles, Champagne labels use a range of terms as described below.

* Level of sweetness:

o Ultra Brut – Bone dry or very dry

o Brut – Dry

o Sec – Literally dry but has higher sugar level than Brut

o Demi-sec – Medium dry

o Doux – Sweet

* Non-vintage: A Champagne made from a blend of wines from different years.

Some Champagne houses may use up to hundred reserve wines from previous years to produce a consistent house style.

* Vintage: A champagne made from a single year’s harvest. The label must show the year of the harvest.

* Blanc de Blancs: This term on the label means that the Champagne has been produced entirely from white grapes, in other words, Chardonnay.

* Blanc de Noirs: Refers to Champagne made from black grape varieties (Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier).

* Rosé: This is often made by blending a little red wine with whites.

* Grande Marque: Means ‘Great Brand’. A producer may use this term but according to AOP rules does not guarantee quality or any style.

* Cuvée de Prestige: These are the top-of-the-range releases from the Champagne houses and may come with a vintage on the label. Some examples include ‘Dom Pérignon’ from Moët et Chandon, ‘Cristal’ from Louis Roederer and ‘La Grande Dame’ from Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin.

* Marque d’Acheteur: Means ‘Buyer’s Own Brand’. These are often seen on Champagnes sold within a retail or supermarket chain that sells them using their own brand name.

Apart from these there are other non-mandatory terms that may appear on the label that specify type of Champagne producers, maturation time etc.

wine-searcher.com