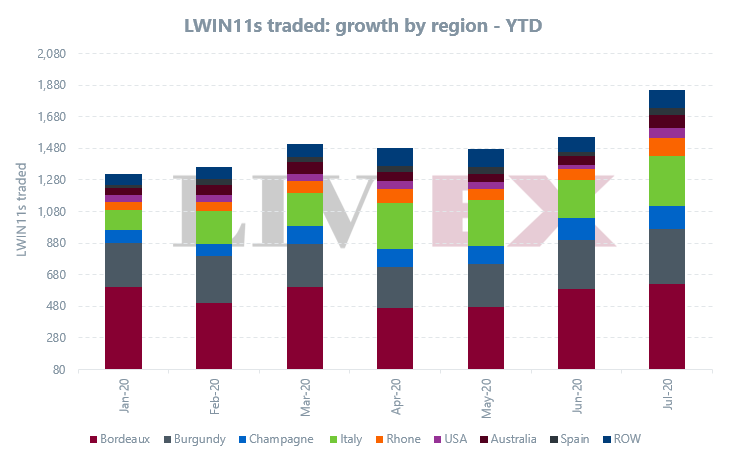

Recently reported, July proved to be a positive month for the fine wine market, due to an ever-broadening array of wines being traded.

Liv-ex states on its website that the number of unique wines traded on the exchange in the first half of 2020 was 37% higher than the same period in 2019.

These are wines marked with code known as an LWIN7, which identifies the producer or brand as well as a specific grape variety or vineyard associated with it.

The second half of the year got off to an even stronger start when the number of wines with an LWIN7 traded in July alone exceeded 1,000 for the first time, 20% higher than the previous record monthly high.

This is due to an on-going broadening of the market at the expense of Bordeaux. Although a vital component of the fine wine secondary market, Bordeaux’s share of trade has been in decline for some time now. January 2020, 46% of unique wines traded on Liv-ex were claret, but by July that figure was down 34%.

At the same time, while Bordeaux has seen the smallest growth in new wines traded, Italy, Spain and the Rhône are recording exponential growth; with unique wines traded up 154%, 153% and 127% respectively since January.

Wines from Austria, Germany, Chile and the Loire have also seen growth (from a small base) and added new and unique wines

Italy of course has been rising for some time now. In October last year it was noted that the number of Italian wines traded on Liv-ex had risen 1,500% in the last 10 years.

Italian wines were also excluded from the 25% import tariffs the US recently imposed on numerous EU produce.

Spain, a small player in fine wine, has seen the number of its unique wines traded rise to match those of the US.

Liv-ex https://www.liv-ex.com/news-insights/

Source: Liv-ex